Items filtered by date: February 2021

In Consultation: Exploring the Inner Selfie: Digital Zen for Young Clients

Credit: Tobi Goldfus

Q: This has been a tough year for my young clients. How do I help them stay centered and connected to therapy, even as most of what they do—and we do—is now online?

A: When I first started doing teletherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic, I worried my young clients would find our virtual interactions awkward, but that was a reflection of my discomfort, not theirs. Having spent a good deal of their life online, they were relaxed during video sessions and delighted to share their safe place, usually their bedroom, with me. They’d point to pictures on the wall or put meaningful objects in front of the webcam for me to see, as if this show-and-tell were the most natural thing in the world. Sharing their space in this way sparked a kind of implicit trust almost immediately.

With Amy, a senior in high school, whose prom had been canceled at the start of the pandemic, I laughed as she grabbed a stuffed animal from her bed and said how Pooh Bear was now more important to her than ever. Her humor was infectious, a sweet release in an anxious time. Our young clients can teach us a lot about adapting and connecting online, but they still need our real-life wisdom about connecting with their core inner selves, especially as they face life’s challenges, whether they unfold virtually or in person.

A Visual Guide to Generalized Anxiety Disorder

What’s Normal?

It's natural to worry during stressful times. But some people feel tense and anxious day after day, even with little to worry about. When this lasts for 6 months or longer, it may be generalized anxiety disorder. Many people don't know they have it. So they may miss out on treatments that lead to a better, happier life.

Credit: Minesh Khatri, MD

Recent Study Examines Grief in Families of Victims of Terrorist Attacks

Terrorism is a crime from which the families of the victims may never recover. A recent study examines the grieving process in depth.

In a recent study, Pål Kristensen, PhD at the Centre for Crisis Psychology at the University of Bergen in Norway and colleagues examined the parents and siblings of the victims of the 2011 terrorism attacks in Norway as they went through the grieving process.1 They found nearly 80% of the study participants had a high level of grief and experienced a slow recovery, if any recovery at all.

“The terror attack in 2011 was a huge national tragedy that affected all of us deeply. Still,

we needed to learn about the long-term mental health effects and how we could help those who were affected the most—the bereaved,” Kristensen said to the press.2

In the aforementioned attack, a far-right Norwegian-born terrorist used a car bomb explosion to kill 8 people in Oslo, then shot and killed 69 people on Utøya Island. Researchers reached out to the family members of these victims; of the 208 contacted, nearly 60% responded.

According to the study, families of terrorist victims are at high risk of developing Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD). PGD is an ailment marked by an intense longing for the deceased, so consistent and severe that it negatively affects daily life.

Credit: Leah Kuntz

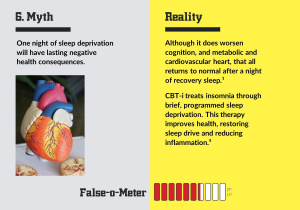

6 Sleep Myths: Experts Weigh In

Ten sleep specialists assessed widely accepted beliefs and here's what they found.

Visit Psychiatric Times to find out more.

Credit: Chris Aiken, MD