Administrator

Neurobiological Underpinnings of Obesity and Addiction: A Focus on Binge Eating Disorder and Implications for Treatment

Obesity has been considered within an addiction framework with the term “food addiction” debated as a potential clinical entity. Certain core addiction characteristics, such as diminished control or loss of control while eating, food cravings, and continued behaviors despite negative consequences, appear pertinent to some patterns of disordered eating. Systematic investigations into neurobiological mechanisms underlying these features are ongoing in an effort to understand potential contributions to different patterns of overeating. It is likely that obesity is the result of multiple factors. Genetics, environment, various overeating behaviors (from excess snacking to overeating of nutrition-poor but calorie-dense foods to binge eating), insufficient lifestyle physical activity, and various metabolic conditions may all contribute in complex ways to obesity.

A central research goal is to define how different etiologies and pathways contribute to the many manifestations of overeating and obesity. Discussing obesity as a unitary disorder may obfuscate research findings that pertain to this complex problem; therefore, our focus is on binge eating disorder (BED).

The notion of food addiction has recently been applied to BED, which is defined by recurrent episodes of consuming unusually large amounts of food. It is important to note that persons with BED experience a subjective sense of loss of control during these episodes, but they do not perform the extreme weight compensatory behaviors that characterize bulimia nervosa. BED is the most prevalent eating disorder; it affects approximately 4% of the US population, occurs across all weight categories, and is strongly associated with severe obesity.1,2It is linked with increased risk of psychiatric and medical comorbidities. Moreover, BED exhibits behavioral and psychological dimensions that are distinct from other eating disorders.

Although BED is currently categorized as an eating disorder in DSM-5, distinct parallels are noted in phenomenological/behavioral features between BED and addiction. Recurrent binging episodes, a lack of control, and personal distress/negative social consequences appear as core characteristics across both disorders. Understanding the neural systems underlying these features is particularly important because they contribute significantly to appetite regulation, weight, and treatment response.

Despite the prevalence and clinical impact of BED, functional and structural neuroanatomical studies specifically examining BED are only beginning to emerge. These neuroimaging studies are fundamental for demonstrating structural and functional brain characteristics supporting BED as a condition distinct from other forms of obesity or other forms of disordered eating (eg, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa). In addition, these studies clarify the clinical relevance of specific features.

Reward processing in BED

Given the frequent consumption of highly palatable foods during binge eating episodes, reward processing needs to be considered in BED. Several neuroimaging studies in BED demonstrate increased activity in prefrontal areas while viewing food stimuli.Specifically, food cues produce greater activity increases in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex/orbitofrontal cortex in individuals with BED than in healthy, overweight, or bulimic cohorts. This region not only processes multimodal information and encompasses the secondary taste cortex, but it also signals the motivational properties of food and other reinforcers, including drugs.Greater activity in the orbitofrontal cortex during food cue exposure relates to higher reward sensitivity, which supports the idea that individuals with BED are hypersensitive to the motivational and rewarding properties of food.Structural differences are also observed in persons with BED: gray matter volume differences have been identified in the medial prefrontal regions in these individuals; this is similar to gray matter volume differences detected in substance-dependent populations.

Palatable flavors (as compared with water) also stimulate greater responses in reward neurocircuitry, including the orbitofrontal cortex, insula, and striatum, in compulsive overeaters.Specifically, high-calorie foods (eg, chocolate milk) produce stronger connectivity between the ventral striatum and other reward regions, relative to water. Higher binge eating scores relate to stronger ventral striatal connections and provide mechanistic information on how BED features might relate to reward-related learning mechanisms.

A reward system that is hyperresponsive to food/taste cues is consistent with the incentive-sensitization hypothesis in addiction that posits that addiction-related cues stimulate and eventually hijack reward neurocircuitry. A large body of research demonstrates that the striatum (particularly the ventral component including the nucleus accumbens) signals reward anticipation.In persons with addictions, the striatum is involved with craving. Understanding whether similar parallels in craving occur in BED and how these may be altered across the course of the disorder is important for future directions.

Understanding responsiveness to non-food reward is also important because generalized reward processing disturbances may play a role in the etiology and maintenance of BED. In contrast to food cues, non-food reward cues (eg, monetary) produce relatively reduced frontostriatal responses in persons who have BED relative to those who do not have BED. Differences in insula activity are also seen in persons with BED. Given the importance of this area in interoceptive processing and homeostatic signalling, individuals who have BED may have difficulties integrating reward information with their bodily state. In persons with BED, anticipation of monetary reward also generates a diminished response in the ventral striatum, relative to non-BED obese individuals.This finding is particularly noteworthy because it parallels reduced anticipatory striatal processing reported in pathological gambling and alcohol-dependent populations, thereby supporting the idea of similar neural alterations underlying reward processing across the disorders.

Longitudinal studies will help clarify whether reduced anticipatory processing represents a precursor for BED development. Nonetheless, these neuroimaging findings are consistent with the idea of a reward deficiency syndrome in persons with BED similar to that proposed in individuals with drug addictions. These findings suggest that blunted reward responsivity may promote the stimulation of the system through behaviors such as drug use, or in the case of BED, eating. In addition, these studies highlight important differences between obese subgroups. Obese individuals with BED and non-BED obese individuals demonstrate significantly different neural responses; therefore, collapsing across obesity subtypes risks obscuring important differences.

Another recent neuroimaging study used brain activation patterns to discriminate various disordered eating groups.Persons with BED had differential activation of insular, striatal, anterior cingulate cortex, and orbitofrontal cortex regions compared with obese non-BED persons, lean controls, and bulimic patients. In this way, increasing evidence supports distinct neurofunctional patterns that discriminate between diagnostic conditions and clinical features.

Cognitive control in BED

A reduced ability or willingness to control the amount of consumption and the frequency of substance intake is a cardinal feature of both addiction and BED. Substance-dependent populations demonstrate reduced recruitment of prefrontal areas during cognitive-control tasks.However, few studies have examined the neurobiological underpinnings of cognitive-control characteristics in BED.

One pilot study of generalized inhibitory processing found diminished activity in frontal areas, such as the orbitofrontal cortex and the inferior frontal gyrus—which subserve self-regulation and inhibitory control—in persons with BED relative to non-BED obese and lean cohorts.Group differences observed here appear driven by the BED group, supporting the idea for distinct cognitive-control differences in BED compared with other forms of obesity. The levels of eating restraint reported in the BED group were related to diminished orbitofrontal cortex and inferior frontal gyrus activity; in contrast, the non-BED obese and lean cohorts demonstrated positive relationships between eating restraint and recruitment of these brain areas. These results demonstrate that within the BED group, there is reduced recruitment of brain areas important for inhibitory control.

Further research is necessary, but these findings nonetheless demonstrate parallel findings with both substance-based and non–substance-based addictive disorders (eg, gambling). And, they support the idea that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex/orbitofrontal cortex areas may contribute to inhibitory-control problems across BED and addictions.

BED treatments and early neuroimaging findings

Emerging evidence suggests that effective addiction treatments might have relevance and may also prove therapeutic for BED. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, has been found to reduce cravings and prevent relapse in alcohol dependence.There is some evidence that naloxone, an opioid antagonist, curtails the duration and magnitude of binge eating episodes.In lean and obese binge eaters, the drug suppresses consumption of high-fat and sugary foods. Similarly, another opioid antagonist—GSK1521498—selectively reduces attentional bias for food cues as well as hedonic preference and consumption of high-fat and sugary foods.

In one of the first pharmacological imaging studies, Cambridge and colleaguesexamined the effects of an opioid antagonist on food-cue response in obese individuals with moderate binge eating symptoms and found reduced striatal (pallidum/putamen) response to highly palatable food-cue images. This study highlights this area as a hedonic hot spot whereby the opioid antagonist disrupts motivational response to food while leaving the hedonic (subjective ratings) unaffected.

These converging lines of evidence suggest the potential utility of testing naltrexone and other opioid antagonists as BED treatment. It must be noted, however, that one randomized clinical trial failed to show that naltrexone had a specific effect relative to placebo for improving eating disorder pathology in women with alcohol dependence.Collectively, however, these early studies suggest that distinct neural systems may underlie motivational versus consumptive aspects of food, and this may prove important for developing treatments targeting core BED characteristics.

Striatal and prefrontal areas emerging as distinguishing BED characteristics also suggest potential dopaminergic mechanisms, since these brain areas represent projection sites of this neurotransmitter. Indeed, dopamine transmission alterations in this reward neurocircuitry are implicated in the transition from substance use to addiction and potentially the shift from overeating to bingeing in BED. A positron emission tomography (PET) study that compared obese individuals with and without BED during food-cue presentations found increased striatal dopamine release following a methylphenidate challenge in the BED group.Interestingly, a higher binge eating score, but not BMI, was related to greater extracellular dopamine release in the caudate during the food stimulation task. This suggests a role for dopamine transmission in binge eating symptomatology rather than weight per se. Thus, striatal dopamine neurotransmission appears important in motivated food behavior, with altered signaling during incentive processing potentially contributing to BED symptomatology.

Controlled treatment studies have found that several pharmacotherapies appear to be effective in BED for reducing binge eating over the short term.However, the longer-term effects of medications for BED are largely unknown or have not yet been shown.

Of the various medications tested for BED, some have not been effective and most have not produced significant weight losses (obesity is not a required feature of the BED diagnosis but is often a comorbid physical problem and weight loss is often considered as a secondary outcome). Two notable exceptions, topiramate and lisdexamfetamine, showed significant and substantial reductions in both binge eating and weight.This year, the FDA approved lisdexamfetamine, a dopamine-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor originally used in the treatment of ADHD, for BED; this is the only FDA-approved medication for BED (fluoxetine is FDA-approved for bulimia nervosa). However, the efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine for obesity have not been established, and the product labeling states that lisdexamfetamine is not indicated for weight loss.

Specific psychotherapies for BED have been shown to have durable effects for up to several years.Cognitive-behavioral therapy is the best established treatment for BED. Strong support also exists for interpersonal psychotherapy and certain forms of behavioral weight loss interventions.However, minimal weight losses have been reported despite robust improvements in core binge eating psychopathology. Combining medication and psychological approaches has generally not enhanced treatment outcomes. Collectively, although treatment research has identified effective approaches, improved interventions are needed because a sizeable minority of patients do not benefit sufficiently, and most patients fail to lose clinically meaningful weight.

Few studies to date have applied neuroimaging to BED treatment; however, these already provide some information on potential treatment targets and mechanisms of treatments. For example, a recent pilot study showed how reward neurocircuitry recruitment relates to treatment outcomes: diminished activity in ventral striatal areas at the beginning of treatment related to persistent bingeing at the end of treatment.Individuals with BED who reported bingeing at the end of a treatment trial demonstrated significantly less activation within reward neurocircuitry (including the inferior frontal gyrus) to non-food reward cues at treatment onset. A study by McCaffery and colleaguesalso found a link between increased inferior frontal gyrus recruitment during food-cue exposure and sustained weight loss.

Future directions

One obvious difference between BED and addictive disorders is the role of the substance in the addictive cycle. Humans are dependent on food for survival. While substantial addiction research is devoted to examining molecular mechanisms of drugs on reward neurocircuitry, the effect of food on these brain regions is less clear. It has been posited that high-fat, -salt and -sugar combinations found in many processed foods may more closely resemble a drug and hijack reward neurocircuitry.Food-drug boundaries may be blurry, since multiple addictive products are derived from natural products; for example, alcohol, an addictive substance, is a natural product from ripe and fermenting grapes that also contains nutrients and calories. More research is necessary for understanding how the hyperpalatability of certain foods may contribute to BED development.

Given the general availability of hyperpalatable foods, some researchers suggest that intermittent access rather than the specific nutritional content of food may be a key factor in the development of bingeing behavior.Nonetheless, animal models suggest an interaction between the access schedule and particularly palatable substances (eg, sugar), since repeated intermittent access to standard food does not necessarily develop into binge eating.

The escalation of binge eating episodes in BED is another behavioral trait that parallels addictive behaviors. In humans, the shift from overeating to BED may result from dopaminergic alterations similar to those seen in addiction. It is noteworthy that PET studies of persons with BED reported dopamine transmission alterations in the dorsal rather than ventral striatum. While the ventral striatum has been implicated in food-cue reward as well as drug-cue reward, the dorsal striatum has been implicated in habit formation and reinforcement of action. However, data also link the dorsal striatum to reward processing in addictions.

Given the different patterns of connectivity of dorsal and ventral striatum, it will be important to understand how ventral and dorsal striatum contribute to BED and how dopaminergic processes may be involved. A challenging but important future direction will be understanding the neurobiology of intermittent access to hyperpalatable foods and how eating restraint may lead to bingeing.

To date, the handful of imaging studies conducted in persons with BED already demonstrate divergent neural substrates of this condition relative to other forms of disordered eating and obesity, substantiating the diagnostic autonomy of BED. This research is also beginning to demonstrate how specific subgroups of obese individuals show neurocircuitry alterations similar to those in other populations characterized by problems with impulse control. Understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of core BED features may clarify distinct and/or overlapping mechanisms with addictive disorders and guide treatment development efforts.

Acknowledgments—This work was supported by P20 DA027844, K24 DK070052, CASAColumbia, and the National Center for Responsible Gaming.

Partners of Veterans with PTSD

Introduction

A number of studies have found that Veterans' PTSD symptoms can negatively impact family relationships and that family relationships may exacerbate or ameliorate a veteran's PTSD and comorbid conditions. This fact sheet provides information about the common problems experienced in relationships in which one (or both) of the partners has PTSD. This sheet also provides recommendations for how one can cope with these difficulties. The majority of this research involved female partners (typically wives) of male Veterans; however, there is much clinical and anecdotal evidence to suggest that these problems also exist for couples where the identified PTSD patient is female.

What are common problems in relationships with PTSD-diagnosed Veterans?

Research that has examined the effect of PTSD on intimate relationships reveals severe and pervasive negative effects on marital adjustment, general family functioning, and the mental health of partners. These negative effects result in such problems as compromised parenting, family violence, divorce, sexual problems, aggression, and caregiver burden. (1,2,3,4,5)

Marital adjustment and divorce rates

Male Veterans with PTSD are more likely to report marital or relationship problems, higher levels of parenting problems, and generally poorer family adjustment than Veterans without PTSD. (2,6,7) Research has shown that Veterans with PTSD are less self-disclosing and expressive with their partners than Veterans without PTSD. (8) PTSD Veterans and their wives have also reported a greater sense of anxiety around intimacy. (7) Sexual dysfunction also tends to be higher in combat Veterans with PTSD than in Veterans without PTSD. (9) It has been posited that diminished sexual interest contributes to decreased couple satisfaction and adjustment. (10)

Related to impaired relationship functioning, a high rate of separation and divorce exists in the veteran population (those with PTSD and those without PTSD). Approximately 38% of Vietnam veteran marriages failed within six months of the veteran's return from Southeast Asia. (11) The overall divorce rate among Vietnam Veterans is significantly higher than for the general population, and rates of divorce are even higher for Veterans with PTSD. The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) found that both male and female Veterans without PTSD tended to have longer-lasting relationships with their partners than their counterparts with PTSD. (3) Rates of divorce for Veterans with PTSD were two times greater than for Veterans without PTSD. Moreover, Veterans with PTSD were three times more likely than Veterans without PTSD to divorce two or more times.

Interpersonal violence

Studies have found that, in addition to more general relationship problems, families of Veterans with PTSD have more family violence, more physical and verbal aggression, and more instances of violence against a partner. (12,2,3) In these studies, female partners of Veterans with PTSD also self-reported higher rates of perpetrating family violence than did the partners of Veterans without PTSD. In fact, these female partners of Veterans with PTSD reported perpetrating more acts of family violence during the previous year than did their partner veteran with PTSD. (2)

Similarly, Byrne and Riggs (12) found that 42% of the 50 Vietnam Veterans in their study had engaged in at least one act of violence against their partner during the preceding year, and 92% had committed at least one act of verbal aggression in the preceding year. The severity of the veteran's PTSD symptoms was directly related to the severity of relationship problems and physical and verbal aggression against the partner.

Mental health of partners

PTSD can also affect the mental health and life satisfaction of a veteran's partner. Numerous studies have found that partners of Veterans with PTSD or other combat stress reactions have a greater likelihood of developing their own mental health problems compared to partners of Veterans without these stress reactions. (10) For example, wives of Israeli Veterans with PTSD have been found to report more mental health symptoms and more impaired and unsatisfying social relations compared to wives of Veterans without PTSD. (5) In at least two studies, including the NVVRS study noted above, partners of Vietnam Veterans with PTSD reported lower levels of happiness, markedly reduced satisfaction in their lives, and more demoralization compared to partners of Vietnam Veterans not diagnosed with PTSD. (2) About half of the partners of Veterans with PTSD indicated that they had felt "on the verge of a nervous breakdown". In addition, male partners of female Vietnam Veterans with PTSD reported poorer subjective well being and more social isolation than partners of female Veterans without PTSD.

Nelson and Wright (13) indicate that partners of PTSD-diagnosed Veterans often describe difficulty coping with their partner's PTSD symptoms, describe stress because their needs are unmet, and describe experiences of physical and emotional violence. These difficulties may be explained as secondary traumatization, which is the indirect impact of trauma on those in close contact with victims. Alternatively, the partner's mental health symptoms may be a result of his or her own experiences of trauma, related to living with a veteran with PTSD (e.g., increased risk of domestic violence) or related to a prior trauma.

Caregiver burden

Limited empirical research exists that details the specific relationship challenges that couples must face when one of the partners has PTSD. However, clinical reports indicate that significant others are presented with a wide variety of challenges related to their veteran partner's PTSD. Wives of PTSD-diagnosed Veterans tend to assume greater responsibility for household tasks (e.g., finances, time management, house up-keep) and the maintenance of relationships (e.g., children, extended family). (13, 14) Partners feel compelled to care for the veteran and to attend closely to the veteran's problems. Partners are keenly aware of cues that precipitate symptoms of PTSD, and partners take an active role in managing and minimizing the effects of these precipitants. Caregiver burden is one construct used to categorize the types of difficulties associated with caring for someone with a chronic illness, such as PTSD. Caregiver burden includes the objective difficulties of this work (e.g., financial strain) as well as the subjective problems associated with caregiver demands (e.g., emotional strain).

Beckham, Lytle, and Feldman (15) examined the relationship between PTSD severity and the experience of caregiver burden in female partners of Vietnam Veterans with PTSD. As expected, high levels of caregiver burden included psychological distress, dysphoria, and anxiety. More recently, Calhoun, Beckham, and Bosworth (1) expanded this understanding of caregiver burden among partners of Veterans with PTSD by including a comparison group of partners of help-seeking Veterans who do not have PTSD. They reported that partners of Veterans with PTSD experienced greater burden and had poorer psychological adjustment than partners of Veterans without PTSD. Across both studies, caregiver burden increased with PTSD symptom severity. That is, the worse the veteran's PTSD symptoms, the more severe the caregiver burden.

Why are these problems so common?

Because of the dearth of research that examines the connection between PTSD symptoms and intimate-relationship problems, it is difficult to discern the exact correspondence between them. (7,16) Some symptoms, like anger, irritability, and emotional numbing, may be direct pathways to relationship dissatisfaction. For example, a veteran who cannot feel love or happiness (emotional numbing) may have difficulty feeling lovingly toward a spouse. Alternatively, the relationship discord itself may facilitate the development or exacerbate the course of PTSD. Perhaps the lack of communication, or combative communication, in discordant relationships impedes self-disclosure and the emotional processing of traumatic material, which leads to the onset or maintenance of PTSD.

Riggs, Byrne, Weathers, and Litz (7) did examine the connection between PTSD symptom clusters and the relationship condition. The study examined the connection between the cluster of avoidance symptoms and the decreased ability of the person diagnosed with PTSD to express emotion in the relationship. The results of the study suggest that avoidance symptoms, specifically emotional numbing, interfere with intimacy (for which the expression of emotions is required) and contribute to problems in building and maintaining positive intimate relationships.

What are the treatment options for partners of Veterans with PTSD?

The first step for partners of Veterans with PTSD is to gain a better understanding of PTSD and the impact on families by gathering information. Resources on the National Center for PTSD website may be useful.

With regard to specific treatment strategies, Nelson and Wright (13) suggest, "effective treatment should involve family psychoeducation, support groups for both partners and Veterans, concurrent individual treatment, and couple or family therapy" (p. 462). Psychoeducational groups teach coping strategies and educate Veterans and their partners about the effects of trauma on individuals and families. Often these groups function as self-help support groups for partners of Veterans. Preliminary research offers encouragement for the use of group treatment for female partners of Vietnam Veterans. (17, 18) Individual therapy for both the veteran and his or her partner is an important treatment component, especially when PTSD symptoms are prominent in both individuals. Couples or family therapy may also be highly effective treatment for individuals' symptoms and problems within the family system. Several researchers have begun exploring the benefits of family or couples therapy for both the veteran and other family members. (14, 19, 20) In light of the recent research on the negative impact of PTSD on families, Veterans Affairs PTSD programs and Vet Centers across the country are beginning to offer group, couples, and individual programs for families of Veterans.

Overall, it seems that the most important message for partners is that relationship difficulties and social and emotional struggles are common when living with a traumatized veteran. The treatment options listed above are but a few of the available approaches that partners may find useful in their search for improved family relationships and mental health.

Additional resources

VA Caregiver Support: The VA Caregiver Support Line (1-855-260-3274) provides services and support to family members who are taking care of a Veteran.

Coaching Into Care: This VA program works with family members who become aware of their Veteran's post-deployment difficulties--and supports their efforts to find help for the Veteran. Contact them at 1-888-823-7458 This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Matsakis, A. (2007). (Sidran Press, paperback, ISBN 1886968187). Back from the Front: Combat Trauma, Love, and the Family. Aphrodite Matsakis is a psychotherapist with a special interest in PTSD. Her book aims to help partners and Veterans understand the effects of combat trauma on relationships and family life. It also includes resources to help every member of the family.

Slone, L.B. & Friedman, M.J. (2008) (Da Capo Press, paperback, ISBN 1600940544). After the War Zone: A Practical Guide for Returning Troops and Their Families. Laurie Slone and Matt Friedman are in the leadership of the National Center for PTSD. Their book is a guide to homecoming for returning Veterans and their families. The book suggests ways families can cope with the effects of trauma.

References

- Calhoun, P. S., Beckham, J. C., & Bosworth, H. B. (2002). Caregiver burden and psychological distress in partners of Veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15, 205-212.

- Jordan, B. K., Marmar, C. B., Fairbank, J. A., Schlenger, W. E., Kulka, R. A., Hough, R. L., et al. (1992). Problems in families of male Vietnam Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 916-926.

- Kulka, R. A., Schlenger, W. E., Fairbank, J. A., Hough, R. L., Jordan, B. K., Marmar, C. R., et al. (1990). Trauma and the Vietnam War generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Silverstein, R. F. (1996). Combat-related trauma as measured by ego developmental indices of defenses and identity achievement. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 157, 169-179.

- Waysman, M., Mikulincer, M., Solomon, Z., & Weisenberg, M. (1993). Secondary traumatization among wives of posttraumatic combat Veterans: A family typology. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 104-118.

- Mikulincer, M., Florian, V., & Solomon, Z. (1995). Marital intimacy, family support, and secondary traumatization: A study of wives of Veterans with combat stress reaction. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 8, 203-213.

- Riggs, D. S., Byrne, C. A., Weathers, F. W., & Litz, B. T. (1998). The quality of the intimate relationships of male Vietnam Veterans: Problems associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 87-101.

- Carroll, E. M., Rueger, D. B., Foy, D. W., & Donahoe, C. P. (1985). Vietnam combat Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: Analysis of marital and cohabitating adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 329-337.

- Cosgrove, D. J., Gordon, Z., Bernie, J. E., Hami, S., Montoya, D., Stein, M. B., et al. (2002). Sexual dysfunction in combat Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Urology, 60, 881-884.

- Solomon, Z., Waysman, M., Avitzur, E., & Enoch, D. (1991). Psychiatric symptomatology among wives of soldiers following combat stress reaction: The role of the social network and marital relations. Anxiety Research, 4, 213-223

- President's Commission on Mental Health. (1978). Mental health problems of Vietnam era Veterans (Vol. 3), pp. 1321-1328. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Byrne, C. A., & Riggs, D. S. (1996). The cycle of trauma: Relationship aggression in male Vietnam Veterans with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Violence and Victims, 11, 213-225.

- Nelson, B. S., & Wright, D. W. (1996). Understanding and treating post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in female partners of Veterans with PTSD. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 22, 455-467.

- Verbosky, S. J., & Ryan, D. A. (1988). Female partners of Vietnam Veterans: Stress by proximity. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 9, 95-104.

- Williams, C. M., & Williams, T. (1987). Family therapy and Vietnam Veterans. In T. Williams (Ed.), Post-traumatic stress disorders: A handbook for clinicians (pp. 221-231). Cincinnati, Ohio: Disabled American Veterans.

- Beckham, J. C., Lytle, B. L., & Feldman, M. E. (1996). Caregiver burden in partners of Vietnam War Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1068-1072.

- Ruscio, A. M., Weathers, F. W., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (2002). Male war-zone Veterans' perceived relationships with their children: The importance of emotional numbing. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15, 351-357.

- Harris, M. J., & Fisher, B. S. (1985). Group therapy in the treatment of female partners of Vietnam Veterans. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 10, 44-50.

- Williams, C. (1987). The veteran system with a focus on women partners. In T. Williams (Ed.), Post-traumatic stress disorders: A handbook for clinicians (pp. 169-192). Cincinnati, Ohio: Disabled American Veterans.

- Johnson, S. M. (2002). Emotionally focused couple therapy with trauma survivors: Strengthening attachment bonds. New York: Guilford.

- Monson, C.M., Guthrie, K.A., & Stevens, S. (2003) . Cognitive-behavioral couple's treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapist, 26, 393-401.

Taken from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treatment/family/partners_of_vets_research_findings.asp

AFOM Ladies Retreat

A few months ago I was trawling through Facebook when I came across this flyer for a weekend away in the Hunter Valley. This ‘Ladies Retreat’ was organised and funded by AFOM, posted by a lady by the name of Gail MacDonell. After a quick spot of research, I found out enough from Google to know that this was a great organisation and I was a little in awe of meeting this OAM recipient. So a little out of my comfort zone, I booked myself into this weekend away and with nervous anticipation headed to Broke to meet and stay with a bunch of random strangers.

But within a few hours of arriving at the lovely Churchview Cottage, these 6 other ladies weren’t strangers at all. They were like minded Defence spouses and Mum’s, and we all had a hell of a lot of things in common! We shared our stories, experiences, struggles and successes. We spent the next day enjoying a festival ‘A Taste of Italy in Broke’ visiting various wineries, stocking up on some lovely local produce and chatting with the friendly folk from the community. We reluctantly said goodbye on the Sunday to head back to our busy lives, promising to do it all again soon.

And that we did, just this weekend gone! The Cheese Lovers Festival at the Sebel in Pokolbin seemed like a perfect chance to book into Churchview Cottage once more and catch up where we all left off!

So what are the highlights and benefits of all this? Well expanding your circle of friends and meeting new ladies in the same situation as yourself, that can completely understand you is invaluable! As Defence families we are used to moving around often and having to make friends quickly. But there’s nothing like listening to others’ stories to put your own issues into perspective to give you some of that sought after appreciation of your own circumstances. Being so warmly accommodated and looked after by the gorgeous Gail and her equally amazing sidekick Ruth Rogers gives you a whole new sense of gratitude. Jumping in the car and driving an hour (or more) out to the open space and peacefulness of the Hunter Valley really means ‘getting away from it all’ which we all want to do sometimes! Only having to worry about yourself for those blissful 3 days leaves you feeling refreshed and recharged, yet not guiltily penniless, as these retreats are graciously funded, so quite affordable on a budget.

Should you have the chance to join one of these AFOM ladies retreats, I would highly recommend you jump in, feet first and with a smile!

Common relationship problems for people with PTSD

What are the most common relationship problems for people with PTSD?

PTSD can affect how couples get along with each other. It can also affect the mental health of partners. In general, PTSD can have a negative effect on the whole family.

Male Veterans with PTSD are more likely to report the following problems than Veterans without PTSD:

- · Marriage or relationship problems

- · Parenting problems

- · Poor family functioning

Most of the research on PTSD in families has been done with female partners of male Veterans. The same problems can occur, though, when the person with PTSD is female.

Effects on marriage

Compared to Veterans without PTSD, Veterans with PTSD have more marital troubles. They share less of their thoughts and feelings with their partners. They and their spouses also report more worry around intimacy issues. Sexual problems tend to be higher in combat Veterans with PTSD. Lower sexual interest may lead to lower satisfaction within the relationship.

The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) compared Veterans with PTSD to those without PTSD. The findings showed that Vietnam Veterans with PTSD:

- · Got divorced twice as much

- · Were three times more likely to divorce two or more times

- · Tended to have shorter relationships

Family violence

Families of Veterans with PTSD experience more physical and verbal aggression. Such families also have more instances of family violence. Violence is committed not just by the males in the family. One research study looked at male Vietnam Veterans and their female partners. The study compared partners of Veterans with PTSD to partners of those without PTSD. Female partners of Veterans with PTSD:

· Committed more family violence than the other female partners

· Committed more family violence than their male Veteran partners with PTSD

Mental health of partners

PTSD can affect the mental health and life satisfaction of a Veteran's partner. The same research studies on Vietnam Veterans compared partners of Veterans with and without PTSD. The partners of the Vietnam Veterans with PTSD reported:

- · Lower levels of happiness

- · Less satisfaction in their lives

- · More demoralization (discouragement)

- · About half have felt "on the verge of a nervous breakdown"

These effects were not limited to females. Male partners of female Veterans with PTSD reported lower well-being and more social isolation.

Partners often say they have a hard time coping with their partner's PTSD symptoms. Partners feel stress because their own needs are not being met. They also go through physical and emotional violence. One explanation of partners' problems is secondary traumatization. This refers to the indirect impact of trauma on those close to the survivor. Another explanation is that the partner has gone through trauma just from living with a Veteran who has PTSD. For example, the risk of violence is higher in such families.

Caregiver burden

Partners have a number of challenges when living with a Veteran who has PTSD. Wives of PTSD-diagnosed Veterans tend to take on a bigger share of household tasks such as paying bills or housework. They also do more taking care of children and the extended family. Partners feel that they must take care of the Veteran and attend closely to the Veteran's problems. Partners are keenly aware of what can trigger symptoms of PTSD. They try hard to lessen the effects of those triggers.

Caregiver burden is one idea used to describe how hard it is caring for someone with an illness such as PTSD. Caregiver burden includes practical problems such as strain on the family finances. Caregiver burden also includes the emotional strain of caring for someone who is ill. In general, the worse the Veteran's PTSD symptoms, the more severe is the caregiver burden.

Why are these problems so common?

The exact connection between PTSD symptoms and relationship problems is not clearly known. Some symptoms, like anger and negative changes in beliefs and feelings, may lead directly to problems in a marriage. For example, a Veteran who cannot feel love or happiness may have trouble acting in a loving way towards a spouse. Expression of emotions is part of being close to someone else. Not being able to feel your emotions can lead to problems making and keeping close relationships. Numbing can get in the way of intimacy.

Help for partners of Veterans with PTSD

The first step for partners of Veterans with PTSD is to gather information. This helps give you a better understanding of PTSD and its impact on families. Resources on the National Center for PTSD website may be useful.

Some effective strategies for treatment include:

- · Education for the whole family about the effects of trauma on survivors and their families

- · Support groups for both partners and Veterans

- · Individual therapy for both partners and Veterans

- · Couples or family counseling

VA has taken note of the research showing the negative impact of PTSD on families. PTSD programs and Vet Centers have begun to offer group, couples, and individual counseling for family members of Veterans.

Overall, the message for partners is that problems are common when living with a Veteran who has been through trauma. The treatment options listed above may be useful to partners as they search for better family relationships and mental health.

Resources

Matsakis, A. (2007). (Sidran Press, paperback, ISBN 1886968187). Back from the Front: Combat Trauma, Love, and the Family. Aphrodite Matsakis is a psychotherapist with a special interest in PTSD. Her book aims to help partners and Veterans understand the effects of combat trauma on relationships and family life. It also includes resources to help every member of the family.

Slone, L.B. & Friedman, M.J. (2008) (Da Capo Press, paperback, ISBN 1600940544). After the War Zone: A Practical Guide for Returning Troops and Their Families. Laurie Slone and Matt Friedman are in the leadership of the National Center for PTSD. Their book is a guide to homecoming for returning Veterans and their families. The book suggests ways families can cope with the effects of trauma.

Sources

Kulka, R.A., Schlenger, W.E., Fairbank, J.A., Hough, R.L., Jordan, B.K., Marmar, C.R., Weiss, D.S., and Grady, D.A. (1990). Trauma and the Vietnam War generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Jordan, B.K., Marmar, C.R., Fairbank, J.A., Schlenger, W.E., Kulka, R.A., Hough, R.L., and Weiss, D.S. (1992). Problems in families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 916-926.

American Article

Relationships and PTSD

How does trauma affect relationships?

Trauma survivors with PTSD may have trouble with their close family relationships or friendships. The symptoms of PTSD can cause problems with trust, closeness, communication, and problem solving. These problems may affect the way the survivor acts with others. In turn, the way a loved one responds to him or her affects the trauma survivor. A circular pattern can develop that may sometimes harm relationships.

How might trauma survivors react?

In the first weeks and months following a trauma, survivors may feel angry, detached, tense or worried in their relationships. In time, most are able to resume their prior level of closeness in relationships. Yet the 5% to 10% of survivors who develop PTSD may have lasting relationship problems.

Survivors with PTSD may feel distant from others and feel numb. They may have less interest in social or sexual activities. Because survivors feel irritable, on guard, jumpy, worried, or nervous, they may not be able to relax or be intimate. They may also feel an increased need to protect their loved ones. They may come across as tense or demanding.

The trauma survivor may often have trauma memories or flashbacks. He or she might go to great lengths to avoid such memories. Survivors may avoid any activity that could trigger a memory. If the survivor has trouble sleeping or has nightmares, both the survivor and partner may not be able to get enough rest. This may make sleeping together harder.

Survivors often struggle with intense anger and impulses. In order to suppress angry feelings and actions, they may avoid closeness. They may push away or find fault with loved ones and friends. Also, drinking and drug problems, which can be an attempt to cope with PTSD, can destroy intimacy and friendships. Verbal or physical violence can occur.

In other cases, survivors may depend too much on their partners, family members, and friends. This could also include support persons such as health care providers or therapists.

Dealing with these symptoms can take up a lot of the survivor's attention. He or she may not be able to focus on the partner. It may be hard to listen carefully and make decisions together with someone else. Partners may come to feel that talking together and working as a team are not possible.

How might loved ones react?

Partners, friends, or family members may feel hurt, cut off, or down because the survivor has not been able to get over the trauma. Loved ones may become angry or distant toward the survivor. They may feel pressured, tense, and controlled. The survivor's symptoms can make a loved one feel like he or she is living in a war zone or in constant threat of danger. Living with someone who has PTSD can sometimes lead the partner to have some of the same feelings of having been through trauma.

In sum, a person who goes through a trauma may have certain common reactions. These reactions affect the people around the survivor. Family, friends, and others then react to how the survivor is behaving. This in turn comes back to affect the person who went through the trauma.

Trauma types and relationships

Certain types of "man-made" traumas can have a more severe effect on relationships. These traumas include:

- Childhood sexual and physical abuse

- Rape

- Domestic violence

- Combat

- Terrorism

- Genocide

- Torture

- Kidnapping

- Prisoner of war

Survivors of man-made traumas often feel a lasting sense of terror, horror, endangerment, and betrayal. These feelings affect how they relate to others. They may feel like they are letting down their guard if they get close to someone else and trust them. This is not to say a survivor never feels a strong bond of love or friendship. However, a close relationship can also feel scary or dangerous to a trauma survivor.

Do all trauma survivors have relationship problems?

Many trauma survivors do not develop PTSD. Also, many people with PTSD do not have relationship problems. People with PTSD can create and maintain good relationships by:

- Building a personal support network to help cope with PTSD while working on family and friend relationships

- Sharing feelings honestly and openly, with respect and compassion

- Building skills at problem solving and connecting with others

- Including ways to play, be creative, relax, and enjoy others

What can be done to help someone who has PTSD?

Relations with others are very important for trauma survivors. Social support is one of the best things to protect against getting PTSD. Relationships can offset feelings of being alone. Relationships may also help the survivor's self-esteem. This may help reduce depression and guilt. A relationship can also give the survivor a way to help someone else. Helping others can reduce feelings of failure or feeling cut off from others. Lastly, relationships are a source of support when coping with stress.

If you need to seek professional help, try to find a therapist who has skills in treating PTSD as well as working with couples or families.

Many treatment approaches may be helpful for dealing with relationship issues. Options include:

- One-to-one and group therapy

- Anger and stress management

- Assertiveness training

- Couples counseling

- Family education classes

- Family therapy

American Article

Depression Overview

Depression: What Is It?

It's natural to feel down sometimes, but if that low mood lingers day after day, it could signal depression. Major depression is an episode of sadness or apathy along with other symptoms that lasts at least two consecutive weeks and is severe enough to interrupt daily activities. Depression is not a sign of weakness or a negative personality. It is a major public health problem and a treatable medical condition.

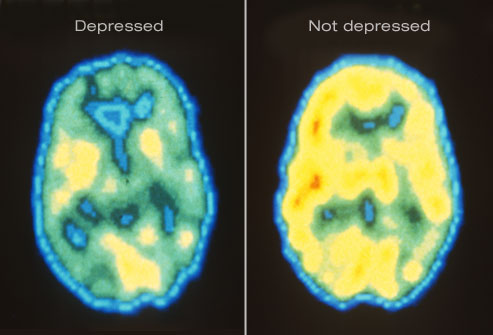

Shown here are PET scans of the brain showing different activity levels in a person with depression, compared to a person without depression.

Depression Symptoms: Emotional

The primary symptoms of depression are a sad mood and/or loss of interest in life. Activities that were once pleasurable lose their appeal. Patients may also be haunted by a sense of guilt or worthlessness, lack of hope, and recurring thoughts of death or suicide.

Depression Symptoms: Physical

Depression is sometimes linked to physical symptoms. These include:

- Fatigue and decreased energy

- Insomnia, especially early-morning waking

- Excessive sleep

- Persistent aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems that do not ease even with treatment

Depression can make other health problems feel worse, particularly chronic pain. Key brain chemicals influence both mood and pain. Treating depression has been shown to improve co-existing illnesses

Depression Symptom: Appetite

Changes in appetite or weight are another hallmark of depression. Some patients develop increased appetite, while others lose their appetite altogether. Depressed people may experience serious weight loss or weight gain.

Impact on Daily Life

Without treatment, the physical and emotional turmoil brought on by depression can derail careers, hobbies, and relationships. People with depression often find it difficult to concentrate and make decisions. They turn away from previously enjoyable activities, including sex. In severe cases, depression can become life-threatening.

Suicide Warning Signs

People who are depressed are more likely to attempt suicide. Warning signs include talking about death or suicide, threatening to hurt people, or engaging in aggressive or risky behavior. Anyone who appears suicidal should be taken very seriously. If you have a plan to commit suicide, go to the emergency room for immediate treatment.

Depression: Who's at Risk?

Anyone can become depressed, but many experts believe genetics play a role. Having a parent or sibling with depression increases your risk of developing the disorder. Women are twice as likely as men to become depressed.

Causes of Depression

Doctors aren't sure what causes depression, but a prominent theory is altered brain structure and chemical function. Brain circuits that regulate mood may work less efficiently during depression. Drugs that treat depression are believed to improve communication between nerve cells, making them run more normally. Experts also think that while stress -- such as losing a loved one -- can trigger depression, one must first be biologically prone to develop the disorder. Other triggers could include certain medications, alcohol or substance abuse, hormonal changes, or even the season.

Illustrated here are neurons (nerve cells) in the brain communicating via neurotransmitters.

Seasonal Depression

If your mood matches the season -- sunny in the summer, gloomy in the winter -- you may have a form of depression called seasonal affective disorder (SAD). The onset of SAD usually occurs in the late fall and early winter, as the daylight hours grow shorter. Experts say SAD affects from 3% to 20% of all people, depending upon where they live.

Postpartum Depression

The "baby blues" strikes as many as three out of four new mothers. But nearly 12% develop a more intense dark mood that lingers even as their baby thrives. This is known as postpartum depression, and the symptoms are the same as those of major depression. An important difference is that the baby's well-being is also at stake. A depressed mother may have trouble enjoying and bonding with her infant.

Depression in Children

In the United States, depression affects 2% of grade school kids and about one in 10 teenagers. It interferes with the ability to play, make friends, and complete schoolwork. Symptoms are similar to depression in adults, but some children may appear angry or engage in risky behavior, called "acting out." Depression can be difficult to diagnose in children.

Diagnosing Depression

As of yet, there is no lab test for depression. To make an accurate diagnosis, doctors rely on a patient's description of the symptoms. You'll be asked about your medical history and medication use since these may contribute to symptoms of depression. Discussing moods, behaviors, and daily activities can help reveal the severity and type of depression. This is a critical step in determining the most effective treatment.

Talk Therapy for Depression

Studies suggest different types of talk therapy can fight mild to moderate depression.Cognitive behavioral therapyaims to change thoughts and behaviors that contribute to depression.Interpersonal therapyidentifies how your relationships impact your mood.Psychodynamic psychotherapyhelps people understand how their behavior and mood are affected by unresolved issues and unconscious feelings. Some patients find a few months of therapy are all they need, while others continue long term.

Medications for Depression

Antidepressants affect the levels of brain chemicals, such as serotonin and norepinephrine. There are many options. Give antidepressants a few weeks of use to take effect. Good follow-up with your doctor is important to evaluate their effectiveness and make dosage adjustments. If the first medication tried doesn't help, there's a good chance another will. The combination of talk therapy and medication appears particularly effective.

Exercise for Depression

Research suggests exercise is a potent weapon against mild to moderate depression. Physical activity releases endorphins that can help boost mood. Regular exercise is also linked to higher self-esteem, better sleep, less stress, and more energy. Any type of moderate activity, from swimming to housework, can help. Choose something you enjoy and aim for 20 to 30 minutes four or five times a week.

Light Therapy (Phototherapy)

Light therapy has shown promise as an effective treatment not only for SAD but for some other types of depression as well. It involves sitting in front of a specially designed light box that provides either a bright or dim light for a prescribed amount of time each day. Light therapy may be used in conjunction with other treatments. Talk to your doctor about getting a light box and the recommended length of time for its use.

St. John's Wort for Depression

St. John's wort is an herbal supplement that has been the subject of extensive debate. There is some evidence that it can fight mild depression, but two large studies have shown it is ineffective against moderately severe major depression. St. John's wort can interact with other medications you may be taking for medical conditions or birth control. Talk to your doctor before taking this or any other supplement.

Pets for Depression

A playful puppy or wise-mouthed parrot is no substitute for medication or talk therapy. But researchers say pets can ease the symptoms of mild to moderate depression in many people. Pets provide unconditional love, relieve loneliness, and give patients a sense of purpose. Studies have found pet owners have less trouble sleeping and better overall health.

The Role of Social Support

Because loneliness goes hand-in-hand with depression, developing a social support network can be an important part of treatment. This may include joining a support group, finding an online support community, or making a genuine effort to see friends and family more often. Even joining a book club or taking classes at your gym can help you connect with people on a regular basis.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) can help patients with treatment-resistant depression that does not improve with medication. VNS is like a pacemaker for the brain. The surgically implanted device sends electrical pulses to the brain through the vagus nerve in the neck. These pulses are believed to ease depression by affecting mood areas of the brain.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

Another option for patients with treatment-resistant or severe melancholic depression is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). This treatment uses electric charges to create a controlled seizure. Patients are not conscious for the procedure. ECT helps 80% to 90% of patients who receive it, giving new hope to those who don't improve with medication.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

A newer option for people with stubborn depression is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). This treatment aims electromagnetic pulses at the skull. It stimulates a tiny electrical current in a part of the brain linked to depression. rTMS does not cause a seizure and appears to have few side effects. But doctors are still fine-tuning this treatment.

Good Outlook

In the midst of major depression, you may feel hopeless and helpless. But the fact is, this condition is highly treatable. More than 80% of people get better with medication, talk therapy, or a combination of the two. Even when these therapies fail to help, there are cutting-edge treatments that pick up the slack.

Taken from WebMD

Two AFOM Directors were selected to tell their stories as part of Australia’s contribution to the Vietnam Veterans Education Centre (VVEC) which is to be built adjacent to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington DC.

The material is being produced by Mullion Creek Productions and will be used for the VVEC and by the Department of Veteran Affairs for future Commemorative and educational purposes.

Firstly Graham Walker AO.

In the late 1970s evidence was coming from the US about troops’ exposure to Agent Orange during the Vietnam war and about what harm that exposure might be causing.

Worried Australian Vietnam veterans formed State Associations seeking answers as to whether their exposure to Agent Orange might cause cancer in themselves and birth defects in their children.

The three institutions that should have keenly embraced these concerns, the government, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the RSL, were dismissive.

- The chemical 2,4,5-T (one of the constituents of Agent Orange) was used extensively in the wheat industry and the government feared veterans’ agitation might threaten this use (seemingly a greater fear then that Australia’s veterans and their children might have suffered harm).

- The Department was in denial despite Repatriation law prescribing veterans claims be given ‘the benefit of the doubt’. Perhaps it was fear of the cost.

- The RSL just went along with the government.

In 1980 the national Vietnam Veterans Association was formed, and under the leadership of Phil Thompson with support from National Research Officer Graham Walker and many others, it campaigned for recognition of the chemicals’ harmfulness.

That campaign included the successful fight for a Royal Commission. But even though the Royal Commission found that, under Repatriation law, exposure could be linked two categories of cancer and that the Department had been guilty of purposely avoiding the ‘benefit of doubt’ provisions of Repatriation law, the Department remained intransigent.

The Vietnam Veterans Federation, under the leadership of Tim McCombe then took the fight to the appeals tribunals (the Veterans Review Board and the Administrative Appeals Tribunal) and won case after case.

Even so, the Department remained intransigent till 1993, when the US Academy of Science findings made further resistance ridiculous.

The medical volume of the Official History of the Vietnam War was published in 1994. It too ignored the Royal Commission findings that under Repatriation law two categories of cancer could be attributed to exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam. It also ignored a Royal Commission finding castigating the Department of Veterans Affairs for failing to obey Repatriation law.

Indeed, the Official History claimed the veterans had no case, were dishonest and motivated by greed. Yet nothing could have been further from the truth.

The Vietnam Veterans Federation since then has campaigned for a new history to be written telling the truth. This campaign has been more difficult because the Official Historian in charge of the Vietnam War series, Dr Peter Edwards and the Australian War Memorial’s chief historian, Mr Ashley Ekins, both strongly supported the original history.

Despite this rather sad and unfortunate support for the original flawed official history’s account, Tim McCombe and Graham Walker, in 2015, convinced the Australian War Memorial Council to commission a new history to re-examine the Agent Orange controversy.

Vietnam veterans are grateful to them.

Dr Peter Yule began this four-year task at the start of 2016.

Dr Gail MacDonell OAM

Dr MacDonell is the wife of a Vietnam veteran. Gail has three children, 9 grandchildren and two great grandchildren

Around 1997 Gail established and ran a support group, for partners of Veterans. Further to that, she decided to study psychology to gain insight into problems of families of veterans that she was encountering on a regular basis. Her PhD (Psychology) researched the psychosocial well- being of partners of Australian combat veterans. She believes that there is a significant interaction between the well- being of the partners/family and health outcomes for the Veterans.

Gail is a Founding member of the Partners of Veterans Association of Australia Inc. and is their first life member. She received an Order of Australia Medal in 2011 for her work with past and present Military families. This work over 18 years has given her a great insight into the issues of not only past but current serving families.

The Australian Families of the Military Research Foundation (AFOM) has grown out of work accomplished by her over the past 18 years. She would like to see AFOM become the foremost organisation in Australia; researching the health and wellbeing of Military Families and assisting Military family members. The name was changed last year into the Australian Families of the Military Research and Support Foundation because of the work Gail and the Foundation are doing within the Military/Veteran Community.

Gail is one that looks and finds the gaps in Services and sets out to fill those gaps. She sees the grass roots issues and has studied in depth all the research around that area as well, and uses that information to work with the families.

Foods That Help or Harm Your Sleep

Indulge Your Craving for Carbs

Carbohydrate-rich foods complement dairy foods by increasing the level of sleep-inducing tryptophan in the blood. So a few perfect late night snacks to get you snoozing might include a bowl of cereal and milk, yogurt and crackers, or bread and cheese.

Have a Snack Before Bedtime

If you struggle with insomnia, a little food in your stomach may help you sleep. But don't use this as an open invitation to pig out. Keep the snack small. A heavy meal will tax your digestive system, making you uncomfortable and unable to get soothing ZZZs.

Get Involved

Our focus areas - research, support and advocacy