Poisonous gas

The experiment began on 22 April 1915. German soldiers, entrenched in the Belgian medieval town of Ypres, attacked with 6,000 steel canisters of chlorine gas. The wind carried the lethal gas, which was two-and-a-half times heavier than air, across to the British enemies, over a front that ran along some four miles. The gas caught the British soldiers unaware, killing 3,000 of them. In no time all of the sides in the war started to set off their own gas attacks: it wafted over battlefields, made it over exclusion zones and wounded more than a million people, killing 70,000.

French troops wearing an early form of gas mask in the trenches during the second Battle of Ypres in 1915. Photograph: Archive/Getty Images

One of the characteristics of poisonous gas, which was banned under international law as a chemical weapon in 1925, is its barbarity. On 10 July 1917 German troops shot blue cross (diphenylchloroarsine) shells, whose ingredients combined to cause victims to sneeze violently, penetrating their gas masks. These were duly called "mask breakers".

The second characteristic is the indiscrimination with which the gas killed. It is impossible to exactly pinpoint this. Whether they were soldiers, citizens or children, each were killed in the same way.

Ronen Steinke, Süddeutsche Zeitung

Shell shock and PTSD

Psychological victims of war are as old as war itself. Deuteronomy, the Greeks and Shakespeare all tell us this. But it wasn't until the first world war that science began to understand this properly and essay the kind of diagnoses that are familiar to us today. Even during the war, some medics still thought that "shell shock" or "war neurosis", as it was known, was down to the physical impact of exploding military ordnance.

But slowly another theory began to form: that the peculiar symptoms exhibited by huge numbers of soldiers (80,000 in the British army alone) was borne of emotional, not physical, stressors – in particular, the almost suicidal nature of the frontline campaign, the close proximity to death, the hideous sight of watching a friend – or enemy – meet a particularly gruesome end.

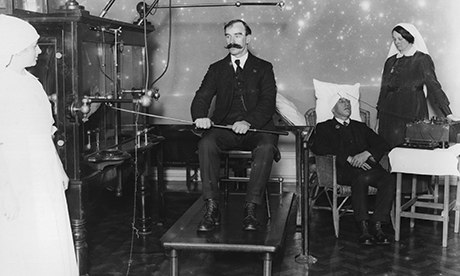

Nurses at the Sir William Hospital using experimental medical equipment on soldiers suffering from shell shock. Photograph: Central Press/Getty Images

Traumatised soldiers shared many common symptoms – from speech difficulties, twitches, anxiety and digestive disorders to more comprehensive nervous indispositions. Doctors found it baffling that these symptoms would often not present until the patient was back in the safe confines of civilian life and why they would persist long after the war was finished.

The vast majority of men did not recover sufficiently to return to the army or the front. Siegfried Sassoon did, but not before he'd written the poem, Survivors:

"No doubt they'll soon get well; the shock and strain

Have caused their stammering, disconnected talk.

Of course they're 'longing to go out again', –

These boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk.

They'll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed

Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died, –

Their dreams that drip with murder; and they'll be proud

Of glorious war that shatter'd their pride …

Men who went out to battle, grim and glad;

Children, with eyes that hate you, broken and mad."

Despite the sudden insights of the first world war, and countless more sufferers in the second world war, it wasn't until 1980 and the aftermath of the Vietnam war that this condition was formally recognised as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Mark Rice-Oxley, the Guardian

Conscription

"Your Country Needs YOU!", the famous poster featuring Britain's secretary of state for war, Lord Kitchener, encouraged more than a million men to enlist to bolster the original expeditionary force deployed to France hopelessly unprepared and unfit for a European war. Within a year of Britain declaring war on Germany in August 1914, despite the numbers of enthusiastic young men who joined up (often with their friends and neighbours in what became known as "Pals" battalions) such was the rate of casualties it was clear the country could not continue to fight by relying solely on volunteers.

For the first time in British history early in 1916 the government introduced conscription. Unlike in many continental powers – including France, Germany, Russia, Austria and Hungary, where compulsory enlistment in different forms had existed for many years, in Britain there was no tradition that citizenship carried military obligations, according to Sir Hew Strachan, Oxford University's professor of the history of War. Strachan made the point in his book, The First World War, that the principle of universal military service was introduced in Britain without the adoption of universal adult male suffrage – Britain had the most limited franchise at the time of any European state bar Hungary.

Photograph: British Library/Robana via Getty

Britain's Military Service Act was passed by parliament in January 1916. It imposed conscription on all single men aged between 18 and 41. The medically unfit, clergymen, teachers and workers employed in key industries were exempt. Conscription was extended to married men in May 1916, and during the last months of the war in 1918, to men up to the age of 51. Conscription raised about 2.5 million men during the war.

Protests against conscription included a demonstration by 200,000 people in Trafalgar Square. Tribunals were set up to hear demands for exemption, including from conscientious objectors. However, the principle of objecting to military service on moral grounds was widely accepted and, in most cases, objectors were given civilian jobs.

The tribunals' main task was ensuring that men not sent to the battlefields were productively employed at home. As the war went on and more men were sent to fight, the shortage of skilled workers in arms factories became more acute. Late in 1917 the German Reichstag passed a law obliging all available males between 17 to 60 to work in arms factories.

An attempt in 1918 to force conscription on Ireland was strongly opposed by trade unions, nationalists and the Roman Catholic hierarchy. It was abandoned and served only to increase support for an independent Ireland (though more than 200,000 Irishmen – Catholic and Protestant – volunteered to serve in the British army).

Canada introduced conscription in its "khaki election" in 1917, the year the US president, Woodrow Wilson, also did so, arguing, Strachan notes, "that it was the most democratic form of military enlistment".

Richard Norton-Taylor, the Guardian

War technology

The war that was supposed to be the one to end all wars was in fact the beginning of all modern conflicts, the origin of the "storm of steel", as described by German officer Ernst Jünger in his memoir of trench warfare.

With the first world war, the technical revolution reached the battlefields and forever changed the way that armies fought. Technology became an essential element in the art of war. It could be argued that it had already been so throughout history (Could the Spanish colonisation of the Americas have taken place without gunpowder? Could Rome have conquered the known world without the superior organisation of its military forces?). However, technology never became so important, and above all, so destructive, although it took many battles and casualties to recognise it.

In Adam Hochschild's essay about the conflict, To End All Wars, he describes how these novelties came upon the battlefields; the submarine and aerial bombardment of civilians, armoured tanks (which weighed 28 tonnes and advanced at the rate of two miles an hour), toxic gas attacks … But, on top of that, the most important innovation was the barbed wire fences, the most definitive and unassuming weapon used, that held the war back to the trenches.